Search the Community

Showing results for 'coal pit lane'.

-

Greenhill Camp airfield 1917-1919

Edmund replied to Postal Historian's topic in Sheffield History Chat

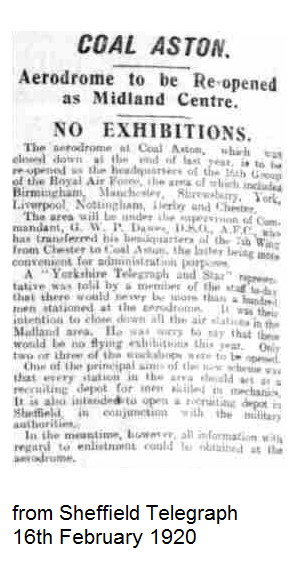

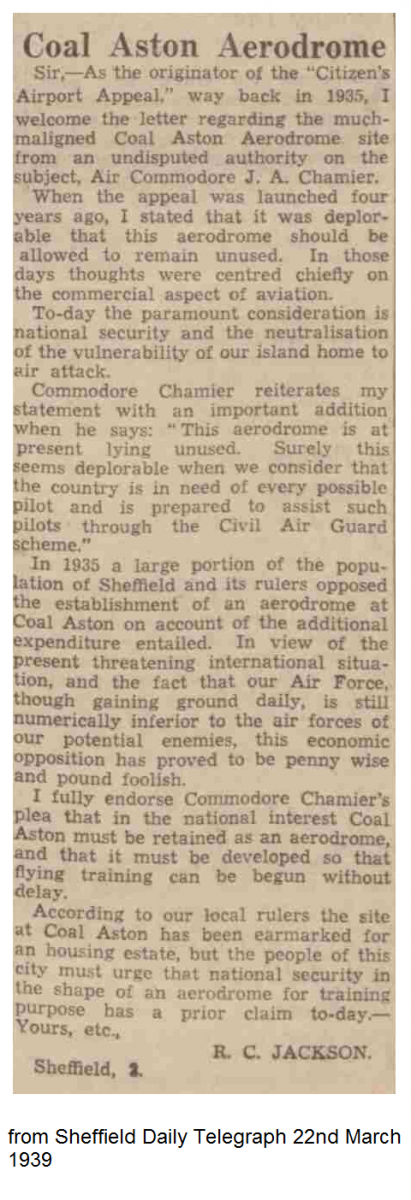

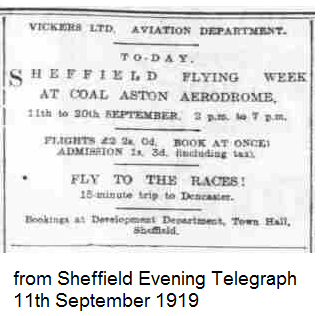

Archives ref 523/3 described as: In August 1919 a successful air exhibition was held at Coal Aston. It was later reported that the aerodrome was to be sold. A conference of local manufacturers was held to discuss the Air Ministry's offer to sell the Aerodrome. Powers were granted in the 1920 Sheffield Corporation Act to buy the site. However the plans came to nothing when in 1922 the government decided that it was not going to grant financial assistance to local authorities to develop civil aviation facilities The Sheffield archives holds ref no CA648 described as: City of Sheffield Municipal Aerodrome Site, comprising: Report by Sir Alan J. Cobham, K.B.E. on An Examination of all land in the vicinity of Sheffield with notes on sites having possibilities and recommendations as to the best possible site for development as a municipal aerodrome; Supplemental report by Sir Alan J. Cobham, K.B.E., on the development of Coal Aston Airport Site, 2 Feb 1931; The Estate Surveyor's, Report on the further acquisition of land and estimate referred to in Sir Alan Cobham Report of 2 Feb 1931; City Treasurer’s Report on Expenditure involved in development of Aerodrome Site at Coal Aston 20 Jul 1931 Further items at the Archives iclude: CA670/7: Copy statement of views of the Air Ministry on the undermentioned sites [Coal Aston and Todwick] that have been suggested for a municipal aerodrome for Sheffield CA621: Correspondence and papers relating to powers under the 1920 Sheffield Corporation Bill for the Corporation to run a municipal aerodrome and the purchase of Coal Aston Aerodrome CA647/32: Report of a meeting between the Town Clerk, City Surveyor and representatives of the Air Ministry regarding Coal Aston Aerodrome Some newspaper articles: -

Spoke to the Coal Authority on this, they were incredibly helpful. Below ground level it has a 5.6mx5.6m cap with an inspection vent pipe, the cap is 75cm thick. The shafts are unfilled as the CA need to go in periodically. It was capped off within the last 26 years. There is also another shaft that is just behind 47/49/51 house.

-

Only the road down to the pit (still to be seen on the 1927 photo) was the Pit Lane. The rest of it belong to Woodthorpe Estate - That of the Hall land, not the modern estate, which wasn't started till the middle 1930's. Even the mine itself at one time started with the Woodthorpe Hall owner. The lane itself was cobblestones and part of it was just covered up when the grassed over area was created. Presumably with the extensive clearing of the land shown in the old Google images they might have dug the cobbles up. One of the images does shows that they attacked the site of the mine itself extensively. And the dark muck shows plenty of coal visible on much of the area. As for the brook itself, I can say that the spring that feeds the stream bubbles up to the surface at the rough patch shown in picture were the curved path is. That would have been at the point of the large pond on the 1927 image. That pond was created by the mine company themselves. That area on the oldest maps was known as the Car Field and so the brook takes it name from that. Of course it's not easy to trace the actual source of the water. Where it first comes up. But there were at least one pond on the land where the Army camp is based. However I can't determine if these were the result of mine workings or spring water coming out. The 1855 map shows shafts on the site. All pits suffer from water getting in them, which has to be pumped out. The "Elm Tree Hill" is the source of at least three brooks. The Car Brook and Kirk Bridge Dike, that flows via Deep Pit. Also the one that flows down by Holybank Avenue at Intake. I don't know if the water is from some giant underground river working it's way to the surface and splitting into sections. Or just several springs coming up at this point.

-

Coal Aston Aerodrome, and Alcock and Brown

lysander replied to Henry Pond's topic in Sheffield History Chat

Coal Aston Aerodrome saw "A" flight of No 33 squadron RFC tasked with the training role but also making nocturnal anti Zeppelin sorties with Home Defence during WW.1. With the signing of the Armistice the airfield found itself being used for aircraft storage. The airfield saw many flying events( Flying Weeks) during the 20's including the previously mentioned Vickers Vimy which made a record flight from Sheffield to London of 95 minutes!!! Most widely remembered were the appearances of Sir Alan Cobham and his "Flying Circus", greeted by Sheffielders in their thousands. In 1920 the Sheffield Act gave the Corporation powers to acquire Coal Aston Aerodrome which figured in the attempts by the Corporation to provide the City with an aerodrome and ancillary services...after promptings by the Air Ministry. The Air Navigation Act of 1920 already empowered the Corporation to build an aerodrome there...but as with so much else, they pontificated.... in 1931 employing Sir Alan Cobham to survey and inspect a total of 9 other sites. In the end, he settled on Coal Aston even though forces were already moving to build the City's southern hospital on the site. Nothing happened and for the sum of just over £3,000.00 the City gave up on an aerodrome and the land ended up being the site of housing,( it has to be said the City Treasurer was unconvinced of Cobham's estimated cost, They suggested a sum of £ 56,131.00 which included the cost of land already acquired by the Corporation.) The site was situated on the 600ft contour line, lying in the Norton/Dyche Lane area and would have had two runways of 900 and 1,300 yards in length . Note it should not be confused with the much later WW2 vintage RAF Norton,,,a barrage balloon depot.( as a matter of interest there exists another Coal Aston landing strip which still receives the very occasional traffic. This is situated close to Apperknowle in NE Derbyshire.) From: The Aviation Wilderness by Stewart Dalton...no longer in print. -

Have looked at the maps of that area on the Scotland map site and it appears it was nearly always part of the Tinsley Wood area most of it's life. There's some evidence of coal working quite close to it, but apart from that there is never been structures in the area to suggest anything for them. Ponds are sometimes associated with mine workings and the nearby one could be evidence of that.

-

The bridge on the old turnpike road in Graves Park is probably a later addition to the turnpike, it is thought that earlier traffic would ford the stream rather than go over it. The stream (Cold Brook) was the source of water for the Wild Well at Norton Hollow. I walked part of the old turnpike route last summer, setting off from the top of Derbyshire Lane, going down through the Park, over the little bridge, up the tarmac lane and out of the park, along Little Norton Lane, down Dyche Lane and up towards Coal Aston, taking a right turn down Green Lane, where I caught the bus to Unstone Green to pick up the trail where it crosses over the river Drone at the old packhorse bridge (dated 1717) the trail goes up Old Whittington Lane, coming out by the Cock & Magpie pub just above Revolution House at Old Whittington.

-

I'm not sure if this adds much more information on Curr's life over that in the excellent article by Ian R. Medlicott from the Transactions of the Hunter Archaeological Society posted by Bayleaf; but it does put Curr's innovations into a wider context. From The Coal Industry of the Eighteenth Century, by T. S. Ashton & J. Sykes, 1929: ...in the working out of the many problems to which this new form of transport gave rise, many engineers played their part, but among them the outstanding figure was John Curr, who for many years occupied the post of viewer to the Duke of Norfolk's collieries in Sheffield. Curr was born, and spent his early years, on the coalfield of Durham, but removed to Sheffield probably in the early seventeen-seventies. At this period Sheffield Park Colliery was let by the Earl of Surrey to Messrs. Townsend and Furniss, who disposed of the coal, according to the usual practice, by sale to the dealers and carters at the pit head. In 1774, however, as the result of an outcry against the high price of fuel, a plan was prepared to convey the coal from the pits to the town by "the Newcastle method", i.e. by a railroad; and this was laid down at a cost of £3280. Whether or not the project emanated from Curr is uncertain, but a few years later, when the colliery was taken over by the Earl of Surrey, Curr was acting as the manager of this and of all the other mining concerns of the Howard family. The most important of his innovations was the substitution for the baskets in which the coal was carried of small four-wheeled corves, which were pushed by boys along tramways in the underground passages. It has been questioned whether Curr actually made use of cast-iron rails below ground before 1790; but a report[1] made by John BuddIe in March 1787 puts the matter beyond doubt; for a comparison of the costs of "the new scheme of hurrying the coals" with those of hurrying with horses includes "Expenses of Cast Iron Plates and Barrow-way". The cost of the old mode was put at 10½d., a waggon-load, that of the new at 6¾d., and it was estimated that the saving at this colliery amounted to £312:10s. a year. There was nothing new in the use of four-wheeled vehicles underground: they had been employed at least a generation earlier in the Newcastle area to carry the wicker corves to the pit-bottom. Curr's innovation was the combination of waggon and corf, the making of a vessel that would run on wheels and could also be raised up the shaft. In Northumberland and Durham baskets were necessary because the bulk of the output was coal in relatively small pieces;[2] and though in the pits about Radstock, in Somerset, the coal was loaded directly into sledges with wicker or wooden sides, it was unloaded into baskets before winding.[3] The new wheeled corf obviated this second handling of the coal, and much bigger loads could be drawn by a horse than when the coal was contained in baskets. To prevent collision between the ascending and descending corves, guides or conductors were devised and patented by Curr in 1788. Two pairs of wooden rails were set vertically upon opposite sides of the shaft, and the ends of a crossbar, to which the corf was attached, ran in the channel between them and so prevented oscillation. The laden corf was raised a little way above the surface, so that a wooden platform could be slid beneath it from which the corf could be run off to the coal stack. A little later further improvements were made by Curr: the rails, which had previously consisted of cast-iron plates fixed on wooden rails, came to be made entirely of cast iron, and instead of the corf being held to the line by a flanged wheel the rails themselves were flanged. Moreover, self-acting inclined planes were introduced both above and below ground, so that the full corves in descending "hurried up" the ascending empties; and a scheme of underground canals was worked out so that the coal could be carried, as at the Duke of Bridgewater's Worsley Colliery, in long, narrow barges from the working face to the pit bottom.[4] Finally, in 1805, Curr applied the steam-engine, for the first time, it is believed, to the purpose of underground haulage. So many innovations soon brought the inventor into repute throughout the country: his wheeled corves came into use at many of the larger collieries; and he was consulted by several important concerns, including the Coalbrookdale Company.[5] Nevertheless, he did not wholly escape the traditional lot of the pioneer. Affairs at Sheffield were not flourishing during the last fifteen years of the century; and in 1787, and again in 1789, John BuddIe was called in to report to Curr's employer on the state of the collieries. The report of 1787 was entirely favourable; and though two years later John BuddIe and John Stephenson felt obliged to recommend the closing of Attercliffe Colliery, they added, "When we think of the Ingenuity and Judicious Application of several late Inventions there adopted ... we feel ourselves hurt as Colliers, in giving a decision so very unfavourable".[6] During the 'nineties irregularities in the seams of coal gave great trouble; about 1795 water from two abandoned collieries found its way into some of the Duke of Norfolk's pits; and severe competition was encountered from a colliery set up in 1793 by a number of sick-clubs of Sheffield.[7] In 1801 John Curr was suddenly dismissed the service of the Duke, without any reason being offered him. In a long letter of protest he set forth the category of improvements which he had effected, and asserted that his own gains had been small. "Now sixteen out of twenty collieries have introduced this mode of conveying coals [he wrote of his tramways] in the Countys of York, Lancaster, Salop, Derby, Staffs., Warwick and a great part of Wales, and is now adopting near London and Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and those who live 10 or I5 Years will probably see my Rail Roads introduced all over this Kingdom, notwithstanding 12 years passed over before they were much imitated". His wheeled corves, his flat-rope winding, and his other contrivances, it was claimed, had been of considerable value to the Duke; and failure to make larger profits was the result of the inroads of water and the price-war with the opposition colliery—"Here my Ingenuity has been buried".[8] Fortunately for Curr, he had other sources of income than the £190 a year which constituted the salary of the viewer. He had royalties from his patents and profits from a foundry which he had set up in 1792 to make the cast-iron rails and boilers and other parts of the new rotative winding engines. An Account Book of 1805 shows that the Duke of Norfolk continued to buy castings and flat ropes of him, and his son seems to have found service at the Duke's collieries. Whether or not Curr prospered, he and his predecessors in the development of the railway certainly deserved well of their fellows; for they did more than any philanthropist of their day to lighten the lot of the most heavily pressed grades of underground labour, the youthful putters and drivers.[9] Not only was the individual relieved, but the proportion of workers engaged in this onerous branch of mining was substantially reduced. At the beginning of the eighteenth century far more labour was employed in moving, than in getting, the coal. At Bo'ness, in 1681, there were 37 bearers to 13 hewers, and at Dunmore, in 1769, 74 bearers to 28 hewers.[10] Even in Northumberland and Durham, where the crude system of bearing had long been given up, there were at Charlaw, in 1769, 10 barrowmen to 10 hewers; and at Stanley Kiphill Colliery the coal hewn by 70 pitmen required the services of 50 putters and 27 drivers to move it to the pit bottom.[11] But, as the direct result of the improvements in underground carriage, by the early years of the nineteenth century the hewers almost always outnumbered the drawers of coal: at Heaton Colliery, in 1806, there were 143 hewers to 84 putters; at Middleton (Yorks), in 1808, 90 hewers to 60 putters; at Washington, in 1813, 67 hewers to 40 putters; and at Gatherick, in 1823, 12 hewers to 6 putters.[12] Such was the immediate result of the work of John Curr. The final result of his invention, like that of Sir Humphry Davy's, was unfortunately less satisfactory. For the wheeled corves could be moved by young children, and though at most places horses were retained to draw a train of corves along the main gates, in some Scottish pits boys were substituted for horses.[13] Moreover, in most of the coalfields the boys and girls who dragged or pushed the wheeled corves from the working places to the underground railways in the main roads were of more tender years than their predecessors who dragged the sledges. [1] Norfolk MSS. [2] Curr, The Coal Viewer (1797), 8. [3] Greenwell and M'Murtrie, The Radstock Portion of the Somerset Coalfield, 6. [4] Report of John Buddie to the Duke of Norfolk, April 7, 1787. Norfolk MSS. [5] Letter of Curr to R. Dearman, May 25, 1793. Horsehay MSS. [6] Report of John Buddie and John Stephenson to Vincent Eyre, Esq., on Attercliffe Common Colliery, April 24, 1789. Norfolk MSS. [7] Letter of John Curr to the Duke of Norfolk, October 23, 1801. Norfolk MSS. The industrial activities of friendly societies are exhibited also in the purchase, in November 1795, of a corn-mill. Sheffield Register (1830). [8] Norfolk MSS., Report of Inventions by John Curr, October 23, 1801. [9] The gratitude of a later generation broke out in verse: God bless the man wi' peace and plenty, That furst invented metal plates; Draw out his years to five times twenty, Then slide him throughout the heevenly gates. For if the human frame to spare Frae toil an' pain ayont conceevin', Ha'e aught te de wi' gettin' there, Aw think he mun gan striate et heeven From THOMAS WILSON, The Pitman's Pay. [10] Barrowman, loc cit. 274–5. [11] Charles Bond in App. B; Bulman and Redmayne, Colliery Working and Management, 40. [12] MSS. in Bell and Watson Collections, Newcastle; Kenneth Vickers, History of Northumberland, xi. 426. [13] "It was when the iron railways came in that they were putting away the horses and brought boys in to draw", Rept. of Child. Empl. Comm. (1842), 363, eve. Geo Lindsay.

-

If the housing was "back-to-back" with a coal cellar, I would think the rear houses would also have a coal-chute. The last "back-to-back" in Sheffield was put up in 1864.

-

This article first appeared in the transactions of the Hunter Archaeological Society Vol 11 p65, and is reproduced here by kind permission of the Society (Notes in [] are listed at the end) THE HISTORY OF GRINDERS' ASTHMA IN SHEFFIELD by M. P. JOHNSON The position of Sheffield, located as it is on the edge of the Pennine range, has always played an important part in the development and growth of the town. The township of: Sheffield, during the greater part of the period under review, was within the much larger parish which included five other townships. [1] The cutlery industry developed within the larger parish. The river Don is the main arterial river, navigable to Sheffield from 1815 onwards by canal. Into the Don flow four other rivers - the Rivelin, Loxley, Porter and Sheaf-all entering from the west. The area looks: Like a man's right hand. If you place your right hand, palm uppermost and your arm in a north-easterly direction with fingers widely spread, you have a rough map of the ancient parish, the fingers being streams running into the Don.[2] It was along all these rivers that Sheffield's industries developed, using water for their source of power, and at least 150 mills were active in 1800.[3] The population of Sheffield, like that of other northern industrial towns, grew very rapidly during the nineteenth century - from 45,000 in 1801 to 324,000 in 1891- and this resulted in the physical expansion of the town.[4] Also like other towns in the industrial north, it suffered from dirt and disease, overcrowding in certain areas and insanitary conditions.[5] Sheffield was within easy access of coal, fringing as it did the South Yorkshire coalfield, and iron ore was close at hand, whilst the moors of the Pennines provided an ample supply of cheap sandstone from which grindstones were made. Cutlery was manufactured by the traditional manual process that involved three main stages - forging, grinding and handlemaking.[6] Forging was the original shaping of the steel to the required pattern, and was performed by one or two men (depending on the size of the object) repeatedly heating and hammering in the forge. Once forging was completed, the blade was passed to the grinder who was normally self-employed, renting a trough in one of the many wheels situated around Sheffield. The mill where the grinding of iron and steel articles was performed was known locally as `the wheel' which was generally the property of one person who let it to different grinders. The various rooms of the wheel were called `hulls'. Each hull contained a number of troughs[7] and any one grinder could have rented one or more troughs, or possibly an entire hull, in which case he would then either have sub-let, or employed apprentices to work the stones. There was complete instability in the wheel, in the sense that it would not be likely that the same group of men would work in the same hull for any length of time - faces would change weekly.[8] In 1794 there were 83 grinding wheels containing 1,415 troughs, employing 1,800 grinders, [9] and a grinder would specialise in one branch of the trade, largely because of the differences in the stages involved and in the sizes of wheels required for grinding different articles. The scythe grinders, for example, were the only ones to have the wheel rotating towards them, while a much larger stone was required for grinding a file than for a penknife blade. The size of the stone could vary from two or three inches in diameter to about six feet. The purpose of grinding was to remove surplus metal, to produce a cutting edge and to obtain a smooth polished surface. The grinder could grind either dry or wet: when wet the stone ran through water in the trough, and saws, files, sickles, table knives, edge tools and scythes were ground in this manner. Forks, needles, brace bits and spindles were entirely dry ground, while scissors and razors went through both processes. During grinding, a dozen quill back razors which weighed 21b. 4ozs. when roughly forged, would be reduced to llb. 15ozs. on the dry stone and to llb. l0ozs. on the wet. [10] Thus, in shaping the razors l0ozs. of steel would be released, and the stone of 7" diameter would be reduced by about 1". Dry grinding was much quicker than wet and became common only during the nineteenth century due to the diminution of wage rates to men paid by the piece.[11] Because there was much more dust thrown into the air during dry grinding, it was a far greater health hazard than its wet counterpart, but if, as was not infrequently the case, wet and dry processes were carried out in the same hull, all men suffered equally. In fork grinding, which was acknowledged to be the worst branch, Dr. G. C. Holland found in 1843 that of 97 men employed, only 30 attained the age of 30 years; and he thus concluded that two thirds of the men died before reaching their thirtieth birthday.[12] In 1865, Dr. J. C. Hall of the Sheffield Public Hospital recorded that the average age of all living fork grinders was 29, scissor grinders 32, edgetool and wool shears grinders 33, and table knife grinders 35. [13] When work was done on a wet stone a large quantity of the dust mixed with the water and was thrown on to the splash back, or fell to the floor, resulting in wet, slippery conditions, but the air was not unbearable with dust, as it was with dry grinding. The stone used was natural sandstone, composed of uniform grains of quartz set in natural siliceous cement. Millstone grit was extensively used in the Sheffield area and the stone would consist of 70-95% silica, 6-15 % alumina with some small amounts of iron titanium oxides, lime, potash and soda.[14] The life of a stone varied, but generally 4-8 weeks was the average in table knife grinding and 2-3 weeks in file grinding. At his stone, the grinder sat on a saddle or horsing built of wooden blocks, so that it was possible to raise or lower it according to the size of the stone. Ablock would be taken out as the stone diminished. The saddle was built up to the stone, almost touching it, and was chainedto the floor in an attempt to give some resistance if the wheel burst - a safety device which was introduced around 1750. After the initial grinding on a sandstone wheel, the article was dried in front of the fire and then passed to the glazier wheel, which was made of wood and could be anything from 4 inches to 4 feet in diameter, covered with leather and dressed with glue and emery. A tremendous amount of dust was thrown up during this process, which was designed to produce a better finish. At the back of the hull was the polisher, another wooden wheel which revolved much slower than the others so as not to generate heat sufficient to ruin the temper of the blade; `Crocus' (iron oxide) was used for polishing, and it was here that the apprentice usually began his training. Many grinders found the dust from polishing far more distressing than that from the stone, because it was much finer. Grinders' asthma, as a disease, developed during the eighteenth century, although grinding had been a part of the manufacture of cutlery as long as cutlery had been made – and most have heard of Chaucer's `Sheffield thwitel' . Until the beginning of the eighteenth century grinding was not a distinct and separate branch of the cutlery trade, but was performed by men who were also engaged in various other departments, with the result that an individual was exposed to a wheel only for short periods.[15] It was the change in the division of labour in the early eighteenth century that led to grinding becoming a distinct occupation, and by 1750, several grinders were observed to have died of a similar complaint that was peculiar to that trade although it was by no means common. Before the nineteenth century conditions of work assisted in making the dust a minimum of nuisance. The men were in large hulls with 6-8 troughs open to the roof, where because of their dependence on water power, the working day in summer was reduced to about five hours, as frequently there was insufficient power to drive the wheel. Furthermore, because of that need for water, the mills were built on the several rivers of Sheffield and could be anything from two to five miles from the town centre. If a man chose to live close to his work he would have the benefit of a cottage with a garden and healthy outlook, where he could spend much of his time in the fresh air during leisure hours and whilst there was a shortage of water. Alternatively, if he lived in town, he would have the benefit of a good walk to and from work - anything up to ten miles per day. The tendency was for there to be no glass in the windows of the wheel, with the result that air could get in and dust could get out, and Holland found that many of the wheels by the rivers were, in the 1840s, well ventilated due to lack of maintenance. Dilapidated roofs, shattered doors and broken or open windows all assisted in the movement of air through the building. [16] The Cutlers' Company, the body governing the cutlery trade until 1814, when an Act of Parliament deprived it of virtually all its powers, had had some influence in controlling ill health. Its restrictions on membership, apprenticeship and the number of working days, although coming under severe pressure in its later days, had been effective in earlier years. [17] Two major changes brought about the growth of the grinders' disease: Firstly the expansion of the dry grinding, which was virtually unknown in the Sheffield area prior to 1700, and only became really prevalent post 1800, and secondly, the introduction of the steam driven wheel, the first of which appeared in Sheffield in 1786.[18] Fifty years later, half of the ninety working wheels were steam driven. By 1908, only eight water wheels were left from a total of over 300.[19] The steam driven wheels were capable of employing much greater numbers of men than were the water driven. Most were two stories high (although some were higher) with a hull containing 8-10 individuals, not necessarily in the same branch of grinding. The largest wheels, Soho and Union, in 1833 gave employment to about 250 people, charging a rent of between 9-17 guineas per annum.[20] The growth of grinding during the nineteenth century took place entirely within the steam driven wheels which were erected in the town - a town rapidly becoming more unhealthy as smoke was churned from chimneys. The new wheels could' be worked all the year round, needing nothing save the efficiency of the steam engine, which was run 14-16 hours per day. The new buildings were waterproof, with glass in the windows, and were generally airtight. The grinder was shut up in a dust filled room for over ten hours per day, almost every day. The number of men who suffered those conditions rose dramatically fro m around 1,800 in 1794[21] to 2,500 in 1819[22] continuing to rise until Dr. Hall counted 5,000 in 1857, with the largest numbers in table, pen and pocket knife grinding.[23] The usual arrangement in the steam driven wheel was to have wet grinding downstairs and the lighter branches upstairs, although there were examples of wet and dry grinding in the same room, in which case the larger articles were at the front, and smaller ones at the back. Grinders' asthma was caused by the grinders breathing in the small particles of dust and metal that he created not only while grinding, but also in other processes essential to his trade. When a stone arrived from the quarry, it was only roughly shaped, and the first task of the grinder was to `race' the stone - that is, to make it round and true. He did that by placing it on its axle in its trough and revolving it slowly, with a steel bar ¾†square and tapered at one end, held up to it. The process could take about one hour for a small stone, and up to six hours for a large one, and was always done dry, even by wet grinders. During `racing' large quantities of silica would fill the air, and the entire hull would suffer. `Rodding' was the holding of a flat iron rod against the stone in order to remove ingrained iron, dirt and other unwanted particles. The skill of the grinder determined how often it was necessary to `rod', but it was not uncommon for `rodding' to be done 30-40 times per day, each occasion taking about ten minutes. If a large piece of metal got embedded in the stone, it would have been necessary, in something like scythe grinding, to take 2-3 inches off a stone six feet in diameter. It was also necessary to smooth the surface of the stone occasionally in order to prepare for `hacking', which was the cutting of a pattern onto the surface of the stone. Notches were cut all round the surface and any `high spots' were removed. Hacking was done with the belt off and so the dust created was not so great. All the operations previously described were performed by both wet and dry grinders, therefore none could escape the dust altogether.[24] Dr. Holland's analysis of 1843 [25] found that in most cases the dust originally settled on the mucous membrane of the air passages, which explained the early symptoms that he found hoarseness, thickening and tenderness about the larynx and trachea, wheezing, a hoarse, dry cough and tightness of the chest. The long-continued irritation prevented the normal procedure of the mucous membrane assisting in expelling the particles, and thus the dust accumulated in the bronchial tubes, and inflamed the then less effective mucous membrane. Eventually, the mucous tissues were permanently thickened and difficulty in breathing resulted. This theory contradicted the accepted idea of the time that dust was limited to the air tubes only, and that it was always removed by the secretions of the mucous membrane. [26] 'However, two structural changes occurred in the body which in many cases helped to prolong the life of the victim. Firstly, there was an enlargement of the bronchial tubes, and secondly, an expansion of pulmonary tissue. The grinder, when he died, frequently exhibited an active inflammation in some of the chest organs, while in some men the pericardium [the sac enclosing the heart] was thickened and adherent to the heart. It was also common for strong attachments between the pleura [the membrane round the lungs] and the internal surface of the thorax to be evident. The apprentice frequently possessed the first signs of the disease - irritation in the larynx, trachea and bronchial tubes, accompanied by a slight occasional cough, but, as these symptoms in no way interfered with the capacities required to pursue his living and daily life, no thought was given to them. Once the preliminary stage of the disease had developed the grinders fell into two categories. Firstly, those who were delicate in stature and had entered grinding at an early age (boys could begin at 8-9 years), were undernourished and living in poor conditions. As grinders they would be scantily clad, frequently having to wear wet clothes (especially if they worked in close proximity to a wet grinder) and thus became easy prey to rheumatic fever. They often worked themselves to a sweat and then immediately went out into the cold. The disease developed rapidly in this type of person, with the several stages very short and death coming early, quite probably linked with constitutional tuberculosis. Alternatively, those of a more robust nature, or who entered the trade later in life, might have the preliminary symptoms for several years before any development occurred. The early symptoms might be seated different places in individuals. If they were in the larynx it caused a change in the tone of voice, whereas in the bronchial tubes they could cause a cough, with possible shortness of breath. As the early symptoms developed, sooner or later the cough and breathing difficulties became more prominent. The body sank forward, taking on permanently that attitude and aspect employed whilst leaning over the stone. The slightest exertion brought with it an extreme shortness of breath, and the man became worried, with a quickened pulse, a regular thick opaque expectoration and pains in the chest aggravated on exertion or deep breathing. The appetite and digestive system continued to function well, and the chest of the grinder sounded well on percussion, a state opposite to that expected in ordinary tuberculosis, where the cough, breathing, and other symptoms were less pronounced. It was at this stage that the grinder and those around him believed him to be suffering attacks of asthma, but post- mortem examination showed that the real reasons were the enlarged bronchial tubes and expanded pulmonary tissue. It was also at that stage that the spitting of blood became a regular feature.[27] In the final stage of the disease the body became permanently bent forward and the shoulders exceedingly rounded. Breathing was short and difficult, while expectoration became more voluminous -very often being black and about the size of a pea. Compared with tuberculosis, there was a more constant, lurching cough, less emaciation and diarrhoea, and virtually no ulcerous condition of the mouth. Once in the above condition, the victim died from long-continued suffering and exhaustion. ' The majority of the grinders suffered a rasping cough for years before any other symptoms developed. When these men died it was noticed that there had been less wasting of the body, less diarrhoea, but more oppressed breathing and voluminous expectoration than in a minority of cases who had virtually no cough or expectoration, but rapid emaciation prior to breathlessness, and a flat contracted chest. The probable explanation of this fact was that some grinders were already suffering from constitutional tuberculosis before contracting grinders' asthma. In these cases, the `asthma' acted as a stimulant and bed for the development of tuberculosis and other complaints. In fact, Dr. Holland recorded that, in a vast number of cases, the asthmatic stage was never really perceptible, but only tubercular wasting.[28] Once weakened, the grinder was subject to pneumonia and pleurisy. The position of the body during grinding allowed the lungs no freedom at all, and that affected the blood circulation. Dr. Holland also found that the grinder was frequently troubled with gravel - a fact for which he could not account.[29] The two types of sufferers were illustrated by Dr. Hall in 1863 as two of his case studies.[30]. The first, the long-suffering grinder, he described as follows: Henry Longdon, aged 53, razor grinder (dry) has worked at Marsden's wheel; used a fan part of his time; worked hard when he was able, but has laboured under grinders' asthma for many years; he is about 5 feet 4 inches; countenance very sallow; hair iron grey; he stoops :a good deal; he complains of the greatest possible difficulty in breathing, has had a cough a great many years and suffered 2-3 time from haemoptysis [spitting or coughing of blood]. The chest measures 32 inches and expands to 32¾ inches, the mobility is greater on the right side than on the left side; there is considerable dullness on both sides of the chest, more particularly on the left, and the surface is a good deal depressed; the movements of the chest, more especially the costal ones [of the ribs], are impaired; the others - posterior diameter and the superficial width of the side, are diminished, and there is a marked parietal resistance [of the chest wall]. The percussion sound in some parts is tubercular and the respiration weak and unequal in quality, harsh and bronchial; in two or three places a dif-fused blowing sound can be heard. The cough was constant; there was not so much expectoration at the time; there was thirst and anorexia [loss of appetite]. The night perspirations were insignificant but the loss of flesh was considerable. He died 4th March 1867. The grinder who suffered only a short period and died early was described in the following manner: Frederick Clark, aged 19, a razor grinder (dry). The disease had made a considerable progress; he had been in the wheel from an early age. He has had a cough and great difficulty in breathing for several years; he states that he has occasionally spit blood; his dyspnoea [breathlessness] is aggravated on the slightest exertion; there is oedema [swelling] of the feet and ankles; the clavicles [collarbones]are prominent, and there is a deep hollow between them and the upper ribs; the respiration is feeble on the left side, and a series of clicking crepit¬ations may be heard during both the respiratory movements; there is a cavity of considerable size at the upper part of the right lung. He died on the first of November, 1854. Post mortem examination showed doctors precisely what had happened in the chest during the illness. Firm, extensive, adhesions between lungs and pleura costalis [part of the parietal pleura lining the chest wall] were visible, and expected, considering the liability to inflammatory attacks of the chest that went untreated even by rest. The bronchial glands, at the forking point with the trachea, were enlarged, and converted into a `black, hard, gritty substance varying in size from half a marble to a large hazel nut'. Dr. Holland then continued his description: In cutting them the sound is precisely the same as if the scalpel were directed against a somewhat soft stone; and when portions are cut away the surface is black and polished, and in passing the edge of the scalpel over it, it grates as if entirely composed of such material. Such masses are commonly detected in grinders who have belonged to the most destructive branches.[31] Similar substances to the above had also been found in the lungs - varying in size from a currant to a bean, whilst in some cases the lungs themselves looked as though blackcurrants had been distributed throughout the whole substance of them[32]. A further frequent occurrence was the presence in the lungs of a black or dark fluid. A portion of a lung of a pen blade grinder was described by Dr.C.Favell in 1843 as follows: The external surface was thickly studded with small black spots about the size of currants. Similar bodies were also discovered in the internal structure of the lungs and here and there they have aggravated so as to form large masses which were very dense and retained the impression of the knife when cut into. In the superior lobe on the left lung, there was a large hardened mass about the size of a hen's egg, which exhibited when incised appearances similar to those already noted. The branches of the vessels, arteries, veins and bronchi were considerably dilated and the lining membrane of the latter much injected. There was a slight emphysima [inflammation] at the edges of the lungs, and at the posterior surface of the inferior lobe. The bronchial glands were enlarged, and of a black colour and several of them contained calcereous matter.[33] Dr. D. Burgess, a surgeon at the Sheffield Public Hospital, found, in 1902, almost identical pathological features to those found by Favell, Holland and Hall in the 1840s and 1850s.[34]. He mentioned the apices of the lungs were more likely than the base to be the seat of nodules that formed black amorphous masses, and in extreme cases the entire upper lobe might be a solid black mass that in section presented a mottled appearance from the innumerable modules, thickened bronchi and pigmented airless lining tissue. He found the pleura adherent to the chest wall and frequently a tubercular cavity at the apex or elsewhere. The treatment available to the grinder was of little value without his taking the initiative and leaving the industry - a thing very difficult to do, although not unheard of.[35] The recommended cure for phthisis [wasting] advertised in The Lancet in 1828 was of little use – a diet of vegetables and milk, warm clothing, a temperature of 60°-68°F and residence in the South of France or Italy.[36] Dr. Holland had a more practical solution, though its effectiveness in providing a cure must be doubted. If the patient attended a clinic in the early stages when he had a cough and expectoration only, and while the chest sounded normal, then Dr. Holland believed the repeated application of six leeches, occasionally followed by blisters, relieved the symptoms.[37] However, it was a rare occurrence for a grinder to see a doctor before he was too ill for work, when, if he would leave the industry, although never regaining his former health, he could be relieved by expectorants, and tonics.[38] The emetics used helped to relieve the bad cough but could produce depression. There was, however, no cure for the pulmonary affections, although the expectorant could help the patient secure tolerable nights. Thus, as the disease developed and got hold in the lungs and bronchial tubes it became impossible to do anything but help relieve the suffering. The most useful emetics and expectorants were tincture of ipecacuanha, which acted as an irritant in the stomach and produced sickness, but which in small doses acted as a stimulant to the mucous membrane of the respiratory passages. Oxymel of squill produced a stimulating effect on the mucous membrane and syrup of poppies relieved a cough. Camphor mixture, mucilage, decoction of liquorice and liverwort were used as the medium.[39] Holland believed the most efficacious combination in the form of pills was equal parts of storax, the compound of ipecacuanha and blue pill, two or three taken at bed time, and one twice or three times per day. There was in former times a reluctance to apply tonics because of the cough and hurried breathing, but Holland would recommend the most powerful vegetable tonics: When we consider that the disease is not one of inflammatory character save the superficially seated inflammation but consists in structural modification such as the enlargement of the bronchial tubes and air cells and thickening and often softening condition of the mucous membrane of the air passages from long continued irritation and condensation of the pulmonary tissue, or a slowly progressive disorganisation of the lungs, tonics will not appear inadmissible.[40] When the normal diet of the grinder was considered tonics were of even greater value. The greatest importance was placed on cinchona used as an infusion and in substance, with some extraordinary results. Sulphuric or nitric acid was usually added to the solution for infusion - whilst in substance it was given in port wine.[41] Holland reported that some patients lived for several years with that treatment, when previously they were on the verge of death. Grinders' asthma apart, the grinder was subject to two other physical problems. The breaking of a stone whilst in use was unfortunately common, causing frightful injuries and even death. Breakages were caused by one of several things, but usually they were within the control of the grinder. The main cause was the wheel revolving too quickly - 3,300 feet per minute was recommended for a wet stone, 4,000 feet per minute for a dry.[42] At that speed any departure from the circular shape would lead to inordinate pressure on parts of the stone, resulting in breakage. It was to counteract that situation that rodding a stone was done so frequently. Further, if a wet grinder allowed his stone to remain immersed in water when it was not in use, the water would soak into the sandstone and considerably weaken it. The earliest method of fastening a stone was by passing the axle through a square hole and wedging it and that gave the stone no support, but from around 1850 plates were used which were clamped to the stone and they were much safer, with far less likelihood of breakage. The second problem was damage to the eyes, for although glasses were available from the 1830s onwards, few grinders would wear them, with the result that frequently a grinder got small particles in his eyes - a fact emphasized by the number of patients attending the specialist eye clinics in the town.[43] It was the grinders' asthma, however, that caused most of the concern throughout the nineteenth century, during which time it was believed that dry grinding was a much greater health hazard than wet grinding, which was thought to he relatively safe. When the statistics collected by Dr. Holland and Dr. Hall in the mid-nineteenth century were examined, the above statement appeared to be true, with the result that the early effort of those interested in the health of grinders was put into making dry grinding, especially that of forks, a safer occupation. In the 1820s, working on what he saw happening to needle grinders in Hathersage,[44], J. H. Abraham invented what he called the `Grinders' Life Preserver' for which he was awarded a gold medal of the Society of Arts in 1822. It consisted of a screen of canvas that divided the room across the grindstone, with an opening directly above the stone, and magnets were placed between the screen and the grinder in order to pick up fine particles of metal. The grinder also wore a magnet round his neck. However, by 1824, only twenty-four grinders were known to be using the `box' of Mr. Abraham's, but when a fan was fitted a little later on, there was a distinct improvement in the number of users. William Calton invented a fan for use in conjunction with Abraham's device, but on the whole, grinders never really took to these methods. For any safety measure to be widely adopted, it had to satisfy three demands. Firstly, it must be acceptable to the grinders. However good it was, if the grinder was not prepared to use it, then it was of no value. Secondly, it must be cheap.[45] The grinder had to rent his hull, and pay for any improvements, and he was unlikely to pay for expensive, health saving machinery. Finally, it must be easy to install and maintain. It was unfortunately the case that, before an efficient widely used system of ventilation was in operation, many men had to die from the grinders' disease. The `asthma' reached its peak during the mid-nineteenth century, with the twenty years between Holland's and Hall's reporting seeing virtually no improvement in the situation at all. There were some good wheels with excellent health records; for example Joseph Rodgers & Sons had a ‘perfect system of ventilation' in 1841, and the Union wheel also had a very good reputation, where Dr. Hall found the average age of death over the period 1859-64 to be forty-six.[46] However, forty years after Abraham's original invention, the vast majority of grinders were no better off than they were before. The need for life saving health improvements in the numerous small grinders' wheels was - particularly emphasized by the work of J. B. White, who wrote the section on grinding in the fourth Report of the Children's Employment Commission in 1865. The report proposed far-reaching safety measures, the restriction of working hours of young persons and the prohibition of grinding for children under eleven. The latter point received general support although the document itself came in for stinging criticism by the Sheffield Town Council who presented a counter report in 1866.[47] The Factory and Workshops Acts of 1857 prohibited work by children under eleven in grinding mills, while the hours of young persons and women were limited to twelve hours per day. Factory inspectors (for the first four years of the Act, the local Sanitary Inspectors) were given the right to enforce the installation of ventilation fans, and the initial work was with the dry grinders, who gradually began to install ventilation systems, but the major hurdle to tight control of this improvement was the lease system. As the workers leased a hull from the owner, and there were several grinders in a hull (and even more in the wheel), it was very difficult to apportion blame and responsibility for not upholding the Acts. Prosecution therefore became irksome and difficult, and it became clear that until the wheel owner was responsible for the ventilation, then little could be done. The 1867 Act was inadequate in many ways, not least in that it was permissive, with the result that in some places, such as Sheffield, the local sanitary authority absolutely refused to administer the Act. Also, nothing had been learned from earlier factory acts, and although the work of young persons and women was regulated to twelve hours per day (6½ hours for children), the period of work might be taken any time between 5 am-9 pm (6 am-8 pm for children), making evasion of the Act, and shift work, very easy. The Consolidating Act of 1878 brought the workshops and factories under the same rules; and in 1901 the Factory and Workshops Act determined that factories and workshops `must be ventilated in such a manner as to render harmless, so far as is practicable, all the gases, vapours, dust and other impurities generated in the course of the manufacturing process or handicraft carried on therein that may be injurious to health'.[48] Also, the Inspector could direct that a fan be installed in a workshop where grinding, glazing or polishing was followed. The most important clause was that the responsibility for the state of the factory or workshop fell upon the owner - not the lessee. Every wheel to be erected after January 1st 1896 was to have at least three feet between troughs in light grinding, or four feet in heavy, with six feet in front of the trough.[49] The Act was designed to relieve the dust problem and to reduce the number of injuries from bursting stones. By 1900 the majority of dry grinders were using a fan, although many failed to maintain them properly, but the condition of the wet grinder had not changed at all during the nineteenth century, and the Act of 1901 had no regulation concerning that branch of the trade. However the most significant decision came in 1908 when the Secretary of State announced that the grinding of metals and racing of stones, was to be classed as a dangerous trade.[50] He went on then to make certain regulations, and from 11th October 1909 it became the duty of those employed in the trade to keep their workshops clean. No dry grinding was to take place without adequate appliances for the interception of dust as near its place of origin as possible. The equipment was to include a hood to catch the dust, a duct sufficiently large and air-tight to do its job efficiently, and a fan to extract the dust. When racing grindstones, respirators had to be worn, and the racing must be done in a room on its own, not to be used again until thoroughly cleaned. There were regulations also concerning the belts and belt races. They had to be cleaned of dust weekly and walls had to be limewashed every 14 months. The emphasis on dry grinding illustrated that even in 1909, that section of the trade was still looked upon as being the worst, although by that date it must have been very questionable as to whether dry grinding was less healthy than wet. The installation of the fan had at last made a significant difference. It was the duty of the tenement owner to provide and maintain 'the fan and duct, the respirator for racing, and be responsible for general cleanliness. Still, soon after the regulations of 1909 had come into force, an enquiryinto the grinding of metals and cleaning of castings was setup. Not having completed its work before the outbreak of World War I, it did not manage to report until 1923, recommencing its enquiries from the beginning after the War.[51] Unfortunately, only five dry grinders from the Sheffield area would allow themselves to be medically tested, and thus the results are not comparable with Hall's or Holland's work. However, the observation of the two reporters, and the general conclusion about grinding, are of value. By 1923, it was known that it was fibrosis or silicosis of the lung that was in fact, being described and, hopefully prevented.[52] The significance of the disease, apart from its effects on the respiratory system, was that it weakened the system and made a ready resting place for tuberculosis, which was the real killer. Thus, although the nineteenth century reformers had been on the right lines in preventing the inhalation of dust, it was necessary to supplement them with other measures. Macklin and Middleton took fibrosis of the lungs as the measure of the affect of the occupation, and found that by far the worst affected, with 73.97% of those examined suffering from it, was the wet sandstone hand grinder. The signs began to appear during the first five years of employment until, after 20 years, nearly 80% were affected. After 40 years all showed signs of fibrosis. The next worst sufferers were the machine wet and dry sandstone grinders, but they were not half way to the average of the wet hand grinders. (These conclusions were arrived at after examination involving chest expansion and stethoscope.) The usual finding when `moderate' fibrosis was present, was a chest expansion of l-2", much diminished air entry over all areas of the lungs but especially the bases, and possibly (though exceptionally difficult to diagnose) a move towards tuberculosis. The grinder himself would complain of dyspnoea. The wet sandstone hand grinders also showed the highest proportion with tuberculosis -7.7% of those examined (compared with 2.76°,% of all others).[53] Bronchial catarrh was worst amongst glaziers and dressers with 27.56% and 25.37% respectively. The wet sandstone grinders showed 14.94% affected - although they were the only group to show any definite relationship between the disease and number of years employed. The incidence was more frequent in early years than later, falling as duration of employment increased. The opposite was true of two related conditions, bronchitis and pulmonary catarrh, and Macklin and Middleton concluded that fibrosis and bronchitis and pulmonary catarrh portrayed the pathological history of the grinder's lung: ... an early fibrosis, insiduous and ingravescent, disabling and at the same time predisposing to tuberculosis on the one hand, or pulmonary catarrh which may be regarded as a form of non-tuberculus chronic pneumonia.[54] The enquiry also distinguished three types of fibrosis, but far the most important was silicosis - a form of fibrosis primarily caused by inhaling silica, related to a high incidence of, and mortality from, pulmonary tuberculosis and non-tuberculous chronic pneumonia. Clearly since the 1860s the health hazard of dry grinding had steadily diminished until by the 1920s, wet grinding, which had previously been considered a 'safe' occupation, was very much in the limelight as an unhealthy job. The introduction of the fan and legal requirements in the hull had saved many dry grinders, but not the wet. It was not possible to use a fan with wet grinding due to the size of the objects ground, the angle of the grinder's body, and the rapid reduction of the stone's diameter. A good cross ventilation was all Macklin and Middleton could suggest as a method of improving the lot of the wet grinder. The major improvements came, however, in the mid and late 1920s. Already by 1923 some branches of grinding had gone over to composite stones - pen and pocketknife blades, razors, scissors and some surgical instruments for example - but some such as sheep shears, scythes, forks, sickles and saws were still firmly entrenched on the old sandstone wheel. If only all could be persuaded to use the silica-free composite stones, grinders' asthma could become a thing of the past. The major stimulant to that move came in 1927 with a `silicosis scheme' which made employers of sandstone grinders liable to pay compensation in cases of silicosis or tuberculosis. [55] Therefore, when insurance rates against this liability shot up 7½% against wages, there was a wholesale change to composite wheels between 1927-9, even though they were ten times as dear, costing between £50 and £60, and lasted only five times as long. Soon, however, mass production brought down the cost of stones. The final change was the use of machinery for grinding, introduced gradually between the two World Wars. Costly, needing a mechanic, and able to use only good standardized forgings, the machine in return offered much quicker work (five gross per day as opposed to one and a half hand ground), a strong metal cover in case the stone burst, and no silica. It was to the composite stone and the machine that the wet grinder could look for his life preserver, just as the dry grinder had looked to the fan. The history of grinders' asthma spanned 200 years, and during that time, thousands of men suffered its effects - usually culminating in death. The dry grinder attracted the early attention of medical men, whose reports stimulated interest and concern for the grinders' plight, but produced nothing in the way of a medical solution. It was left to technological innovation, with the development of the fan, to remove the worst evils of dry grinding. Only with the national improvement in life expectancy around the turn of the last century did it become appreciated that wet grinding was also a serious health hazard. Although medical progress had been made, still no cure was forthcoming, and it was again left to technological advancement to prevent, rather than cure, the grinders' asthma. Thus a disease that was unknown in 1750 had almost completely disappeared by 1950. NOTES 1 These were Upper Hallam, Nether Hallam, Ecclesall, AttercIiffe-cum-Darnall and Brightside. They were locally known as Bierlows. 2 Edward R Wickham, Church and People in an Industrial Society, London, 1969. p.17. 3 For details of these, see W T. Miller, The Water-Mills of Sheffield, Sheffield, 1949, 4th ed. 4 See Population Tables, H.M.S.O. 1852, Vol. 2 Division IX p.8. for 1801-1851. Thereafter, Decennial CensusReturns, .M.S.0.1861,1$71,1881,1891 and 1901. Reprinted byIrishUniversityPress,1970:¬ 5 This was at its worst between cI840-1870. See for examples J. Hayward and G. Lee, Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Borough of Sheffield, Sheffield, 1848, and S. Pollard, History of Labour in Sheffield, Liverpool, 1959. 6 See G. I. H. Lloyd, The Cutlery 'Trades, London, 1913, reprinted 1968, chapter 2. 7 The word trough had two meanings. Strictly speaking itwas a cast iron container sunk into the floor; which held the water for wet grinding and into which the stone just dipped. In a broader sense it included all the grinding wheels behind the original trough containing the grindstone. Hence, every¬thing in one belt race became known as the `trough' or `trow'. 8 Hirers paid a weekly rent which covered the cost of power used and any artificial light. As the grinder may be a subtenant, an employee or a `master' it was difficult to maintain any stability. See H. Lush, Report to H.M. Secretary of State for Home Department or Draft Regulation Proposed to be made for Factories in which Grinding of Metals and Racing of Grindstone is Carried on, H.M.5.0., 1909, p. 3. 9 G. I. H. Lloyd, op cit, pp. 443; 157. 10 J. C. Hall, On the Prevention & Treatment ofSh.effield Grinders' Disease, London, 1957, p. 16. 11 G. C. Holland, Diseases of theLungsfrom Mechanical Causes, London, 1843, p. 2. See also A Knight, `On the Grinders' Asthma', in North of England Medical & Surgical Journal, 1830, pp: 857,170-179 12 G. C. Holland, Vital Statistics of Sheffield, London, 1843, p. 193. Dr. Holland was very concerned about the incidence of grinders' asthma in the 1830s and 40s and did considerable research into the disease. 13 J. C: Hall, Trades of Sheffield as Influencing Life and Health and more Particularly File Cutters & Grinders, London, 1866. Also J. C. Hall, Prevention, p. 22. 14 E. L. Macklin and E. L. Middleton, Report on the Grinding of Metal and Cleaning of Castings with Special Reference to theEffects of dustlnhalation upon the Workers, London, H.M.S.0.;1923, p. 6. 15 See G. I. H: Lloyd, op. cit., p. 157. Also, A Knight, op cit, p. 86. 16 A Knight op. cit., p. 86. Also G. C. Holland, Diseases, p. 2. 17 In 1814, 54 George 111 Cap. 119 left the Company with virtually no powers at all, and had the effect of opening all branches of the cutlery trade to anyone who wished to participate. There were no longer any regulations on the number of apprentices to be employed. This dearly left a vacuum that the trade unions tried to fill in the 1850s; and 1860s, resulting in the'Sheffield Outrages'. For further details on the Cutlers Company, see G. I. H. Lloyd, op. cit., Chap. 5, and R E. Leader, The Cutlers Company ofHallamshire in the County of York, Sheffield, 1905-6. 18 A Knight, op. cit., P. 87, 19 G. I. H. Lloyd, op. cit., p. 179. 20 J. C. Hall found in 1857 the Soho wheel employed 500 men and boys in 50 hulls and the Union wheel 300-400 men and boys in 46 hulls. These were the biggest wheels and, it would appear, the best regulated. J. C. Hall, Prevention, p. 22. 21 G. I. H: Lloyd, op. cit., p.157. 22 A Knight, op. cit., P. 87. 23 J. C. Hall, Prevention, p. 22. 24 E. L. Macklin and E. L. Middleton, op. cit., p. 24. 25 G. C. Holland, Diseases, p. 4. 26 A Knight, op. cit., p. 171. 27 Several doctors in the Sheffield area were involved with the grinder and published the results of post-mortem analyses: See for-example,: J. S. Waterhouse, 'Contribution Towards the Pathology of Grinders Disease of the Lungs' in Provincial Medical Journal No.155,16th September 1843, 499-503; E. D: L. Gilliatt, `Post Mortem Appearances in a Case of Grinders' Asthma' in The Lancet, 1842, p. 408, as well as the works referred to by J. C. Halt and G. C: Holland. 28 G. C. Holland, Diseases, p. 22. 29 ibid, p. 26. 30 J. C. Hall, Prevention, pp. 39-41. 31 G. C. Holland, Diseases, p. 41. 32 ibid, p. 41. 33 C. Favell, B.M.J., 4th Nov. 1843, No. 162, p. 100. 34 Dr. D. Burgess wrote the account of the pathology and symptomology of grinders disease in S. White; `Steel Grinding', in T. Oliver's Dangerous Trades, London, 1902, pp. 409-10. 35 See for example G. C. Holland, Diseases, p. 49, also A J. Knight, op. cit., pp. 170, 172. There seemed to be a rather reckless attitude to the problem, shown by the grinders themselves. J. C. Hall quotes a grinder aged 26 saying `that he reckoned in about 2 more years at his trade, he might begin to think of dropping off his perch' adding `a fork grinder is an old crock at 30'. 36 The Lancet, April 261828. 37 G. C. Holland, Diseases, p. 46. 38 Ibid., p. 48, also A J. Knight op. cit., p. 173. 39 Ipecacuanha is the root of a Brazilian shrub containing emetics and alkaloid Squill is a Mediter¬ranean bulb. 40 G. C. Holland, Diseases, pp: 48-9. 41 Cinchona is quinine which is more soluble in acid than water. 42 E. L. Macklin and E. L. Middleton op. cit., pp. 42-3. 43 The number of private eye clinics in the town grew from 0 to 3 in the 1830s. By the 1860s the General Infirmary had a specialist eye department. 44 The average age of death of needle grinders was 19. 45 Hall says a good fan cost between £1.lOs and £3 in 1857. 46 G. C. Holland, The.Mortaliry, Suffering &-Disease of Grinders, London, 1841, p. 15. The proportion of diseased to healthy was 21 : 1. The average age of death at Joseph Rodgers & Sons 1850-65 was 29 years (43 for dry grinders only) and this compared with the following averages for the area: fork grinder 29, scissor grinders 32, edge tool grinders 33, table knife grinders 35. 47 The Council did not accept White's general conclusion taken from specific instances; and there was also some question as to whether or not White had lost some of his notes. Thus in the petition to the Queen re the White Report, the Council claimed: l. Mr. White lost part of his notes. 2. Council evidence contradicted Mr. White's. 3. There were some irregularities in the employment of children but most young children at grinding wheels were not employed, `but just with their fathd'. Their suggested changes in the law were: (a) To prohibit the employment of children under 12. ( To provide for fencing of machinery. © To prohibit dry grinding without a fan. (d) To make it compulsory for grindstones over 3ft. 6 inches in diameter to be fixed to the axle by plates. See Pollard, op. cit., p. 151 Sheffield Independent, 9 Dec. 1865, 7 Feb. 1866, 23 Sept. 1865, 28 October 1865 and 22 Sept. 1865. Also, Sheffield Council Minutes, 8 Dec. 1865. 48 Quoted by E. L. Macklin and E. L. Middleton, op. cit., p. 77. 49 See A- H. Lush, op. cit., pp. 2; 12. 50 The Act of 1901 gave the Secretary of Trade power to declare certain industries `dangerous'. By a certificate, dated 14 October 1908 the process of grinding of metals and racing of grindstone was declared dangerous. Quoted in Macklin & Middleton op.cit.,p.78 51 E. L. Macklin and E. L. Middleton, op. Cit., See also A. H. Lush, -op. cit. 52 See 5. Pollard, op cit., p: 284: ,Also A: I. G. McLaughiin Industrial Lung Diseases of lron and Steel Workers, 1950. 53 Ibid, p. 54. 54 ibid, p. 73. 55 Metal Grinding Industries (Silicosis) Scheme, 1927. S. R &y 0, 1927. No. 380.

-

Further to my little mention of Dent Main Colliery, and the interest that is shown in the Colliery, I would like to share the following information that was given to me in a meeting with the daughter of one of the Collieries Directors. Mr Brian Hutchinson went into partnership with Colin and Albert Pemberton and opened the pit in 1924. The entrance to the drift was set back 100 yards from the main Birley Moor Road at the bottom of Birley Wood. The drift was driven at an incline if 1 in 3.3 into the Parkgate seam of coal. In 1945 the Colliery employed 27 men underground and 11 on the surface, and at this time the manager was Mr J H Heslop. In 1947 when the mines were nationalised the N.C.B granted the pit an operating license. Because the Colliery was gas free the miners were allowed to use acetylene lamps as working lights. There were no mechanical means of Coal getting, so holes were drilled into the coal face along its length,and shots were fired which brought down the coal when it was worked by pick and shovel and loaded into tubs which were of 10 cwts capacity. Pit Ponies were used to transport materials to the coal face, and to bring full tubs of coal to the bottom of the drift where they were attached to a haulage rope to be hauled to the surface by a petrol engined winch. on reaching the surface the tubs were derailed by one man using a long pole, tipping the coal onto a screening belt,the man then joined two others to sort the coal until the next tub arrived on the surface. Dent Main was one of the last pits in the Sheffield are to use ponies, they were well looked after and regularly taken to Hackenthorpe village Blacksmiths to be re shod. The pit was known locally as Diamond Row Pit because of the close proximity of a row of miners cottages ,all of which had diamond design leaded windows. The workings at the Colliery were always in orange coloured "Ochre Water" due to the iron deposits in the workings, the water being continually pumped from the pit. The pit was very successful and supplied the local steel works in Sheffield ,and the Collieries own two lorries took coal to Blackburn Meadows Power Station at Meadowhall ,Sheffield. Mr Brian Hutchinson was the sole remaining director when the Colliery closed in the early 1970s. He was the one who drew up the plans for the workings in all areas of the mine,great credit due to him as the only instrument available to him at the time was a hand held compass.The compass and the Colliery maps are the only remaining artefacts to have survived, and are the proud possessions of his daughter Mrs Margaret Bennett who gave me permission to tell the story for future generations. KEN.

-

https://www.nmrs.org.uk/assets/mines/coal/yorkshire/1854/S.html

-

Some fascinating shots there of the pit just after it’s closure. The area with the concrete and the old coal tub looks as if it was just beyond the pictures. I’m assuming they dragged all the waste up out the way once they built the houses. About 15 years ago I do recall there being a pile of bricks in the same area which seems to have disappeared, again presumably from one of the numerous brick small sheds located in the area.

-

Victoria Quays, Sheffield City Centre

Sheffield History replied to Sheffield History's topic in Sheffield History Chat

Victoria Quays (formerly Sheffield Canal Basin) is a large canal basin in Sheffield, England. It was constructed 1816–1819 as the terminus of the Sheffield Canal (now part of the Sheffield and South Yorkshire Navigation) and includes the former coal yards of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway. The basin ceased operation as a cargo port in 1970 and the site and buildings were largely neglected. A restoration and redevelopment of 1992–1994 reopened the site providing new office and business space and leisure facilities as well as berths for leisure canal boats. There are a number of Grade II listed buildings on the site. These include the original Terminal Warehouse of 1819, the Straddle Warehouse (1895–1898), a grain warehouse (c. 1860), and a curved terrace of coal merchant's offices (c. 1870). -

The Sheffield area was once a tropical swamp forest!

lysandernovo replied to John Russell's topic in Sheffield History Chat

In the days when we used coal to heat our homes many a young fossil hunter would find examples of fossilised tree leaves and ferns in the household coal....that's how I started a life time interest in geology...passed onto my son who became a geologist! -

Birley East Colliery Silkstone seam abandoned 1934 Coal production ceased completely November 1943 Training centre opened and training commenced December 1943 Training stopped June 1948 Birley East branch line closed 1950 Underground and surface quipment stripped out and buildings demolished 1950-1952 Downcast shaft filled to surface Feb 1963 Upcast shaft filled to surface May 1986 Both shafts capped February 1990 Training centre buildings on Beighton Road demolished 1998

-

Was William also a coal dealer? Simpson William, cowkeeper and coal dealer, New George Street. From White's directory, published 1862.

-

Old Maps website is closing down on 31 October 2021

DaveP replied to RLongden's topic in Sheffield Maps

Such a pity Oldmaps.co.uk have several maps that Ive never found on other map sites, particularly earlier than 1900, always seemed damned expensive to subscribe just to zoom in and still be restricted to 300 maps per month. I shall miss this site greatly, was a tremendous help in locating old pre 1900 coal mines -

Pedestrians and Traffic 1950

Unitedite Returns replied to madannie77's topic in Sheffield History Chat

Coal was still the principle source of heating used in most households at that time, gas was still produced from coal, most electricity power stations were gas-fired, the principle form of propulsion on the railways was still steam generated from coal, as was indeed, the energy source that powered most of those industries still prevalent at that time, and indeed, some of the fuel used in internal-combustion engines was being generated from coal-shale. The first clean-air act wasn't passed through parliament until 1956, so I suppose that some haze would have been present in most major conurbations most of the time. However, you certainly do get the distinct impression, that when in public, that there was a tendency for people to pay much greater attention to their appearance than perhaps we do today. Brilliant footage by the way. Much enjoyed watching it. -